|

| Panciteria Macanista del Buen Gusto |

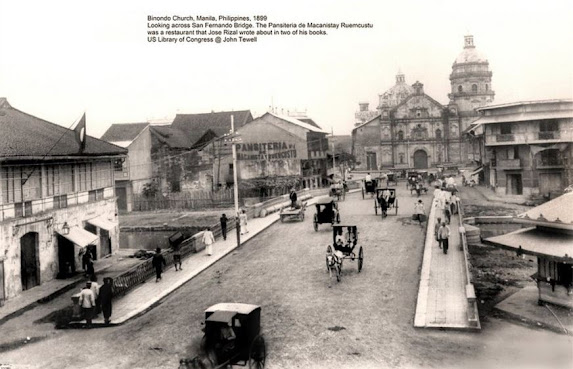

On my way back to Binondo Church, I crossed San Fernando Bridge again. I remembered that in old photographs, the ruined building on the left side, at the foot of the bridge, was the site of a restaurant. A wall used to carry a huge sign that read: “Panciteria Macanista del Buen Gusto” (Macanese Panciteria of Good Taste), which was referenced in Chapter 25 of “El Filibusterismo.” As Rizal described it: “At the center of the sala and beneath the red lanterns were four round tables, systematically arranged to form a square; equally round little wooden stools served as seats. In the middle of each table, according to the custom of the establishment, were laid out four small colored plates with four pastries on each one, and four tea cups with their corresponding lids, all of red porcelain. In front of each stool could be seen a bottle and two wineglasses of gleaming crystal.”

|

| Panciteria Macanista del Buen Gusto |

Sandwiched between two buildings in Binondo, Manila is a decrepit century-old structure said to be a Spanish-era panciteria that was mentioned by Jose Rizal in the novel "El Filibusterismo."

This crumbling wooden building with its dilapidated capiz shell windows is believed to be the Spanish-era restaurant "Pansiteria Macanista de Buen Gusto" famous back when Binondo was a bustling commercial district.

The building looked out of place between an Asia United Bank building in front of the Plaza San Lorenzo Ruiz, and the San Fernando building, tucked in a corner of Juan Luna and San Fernando streets in front of the Binondo church and just beside a bridge.

Rizal, whose execution the country commemorated on Monday, Dec. 30 , wrote of the panciteria as the venue of a meeting of 14 students where they ate "pancit lang-lang" while mocking the Spanish friars, in Chapter 25 of "Fili" entitled "Smiles and Tears."

The panciteria is an 1880s structure then owned by a certain Don Severino Alberto, according to Stephen Pamorada of the Heritage Collective, citing Lorelei de Viana's book “Three centuries of Binondo architecture, 1594-1898: A socio-historical perspective.”

The building is now owned by Ever New Realty and Development Corp. located in San Nicolas, Manila, Pamorada said.

For now, the building is a "Presumed Important Cultural Property" having been over 50 years old, said architect Wilmer Godoy of the NHCP Historic Preservation Division, which means it is protected from being demolished.

“Status of the structure is not yet officially declared both in national and local levels. Only that it has presumption of an important cultural property under the National Cultural Heritage Act, since it's a 50 plus-year-old structure,” Pamorada explained.

Tito Encarnacion of the Advocates for Heritage Preservation expressed hope the government would take steps to preserve the heritage building since a beautiful white Spanish-era building just in front of the panciteria was recently demolished. “It is definitely a heritage structure that is worth preserving. It is in a state of advanced deterioration. If no intervention will be done on it, it may just collapse soon,”

|

| Panciteria Macanista del Buen Gusto along San Fernando Bridge, Binondo Church on the right. |

Bento Box:

El Filibusterismo, Chapter XXV: Smiles and Tears

The sala of the Panciteria Macanista del Buen Gusto that night presented an extraordinary aspect. Fourteen young men of the principal islands of the archipelago, from the pure Indian (if there be pure ones) to the Peninsular Spaniard, were met to hold the banquet advised by Padre Irene in view of the happy solution of the affair about instruction in Castilian. They had engaged all the tables for themselves, ordered the lights to be increased, and had posted on the wall beside the landscapes and Chinese kakemonos this strange versicle:

“GLORY TO CUSTODIO FOR HIS CLEVERNESS AND PANSIT ON EARTH TO THE YOUTHS OF GOOD WILL.”

In a country where everything grotesque is covered with a mantle of seriousness, where many rise by the force of wind and hot air, in a country where the deeply serious and sincere may do damage on issuing from the heart and may cause trouble, probably this was the best way to celebrate the ingenious inspiration of the illustrious Don Custodio. The mocked replied to the mockery with a laugh, to the governmental joke with a plate of pansit, and yet—!

They laughed and jested, but it could be seen that the merriment was forced. The laughter had a certain nervous ring, eyes flashed, and in more than one of these a tear glistened. Nevertheless, these young men were cruel, they were unreasonable! It was not the first time that their most beautiful ideas had been so treated, that their hopes had been defrauded with big words and small actions: before this Don Custodio there had been many, very many others.

In the center of the room under the red lanterns were placed four round tables, systematically arranged to form a square. Little wooden stools, equally round, served as seats. In the middle of each table, according to the practise of the establishment, were arranged four small colored plates with four pies on each one and four cups of tea, with the accompanying dishes, all of red porcelain. Before each seat was a bottle and two glittering wine-glasses.

Sandoval was curious and gazed about scrutinizing everything, tasting the food, examining the pictures, reading the bill of fare. The others conversed on the topics of the day: about the French actresses, about the mysterious illness of Simoun, who, according to some, had been found wounded in the street, while others averred that he had attempted to commit suicide. As was natural, all lost themselves in conjectures. Tadeo gave his particular version, which according to him came from a reliable source: Simoun had been assaulted by some unknown person in the old Plaza Vivac, the motive being revenge, in proof of which was the fact that Simoun himself refused to make the least explanation. From this they proceeded to talk of mysterious revenges, and naturally of monkish pranks, each one relating the exploits of the curate of his town.

No comments:

Post a Comment