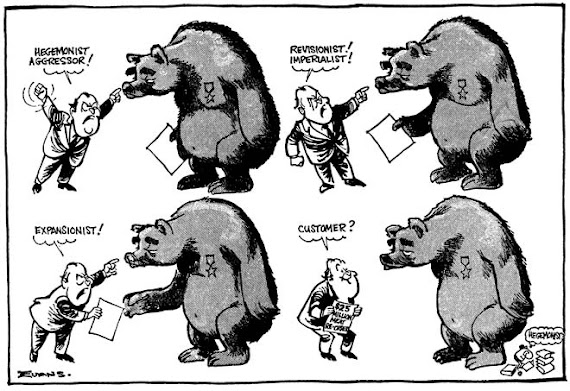

“There is a widening consensus about supplying Ukraine howitzers and more complex weapons systems, and everyone is now doing that,” Mr. Heisbourg noted.

“But it’s another thing to pivot the war aim from Ukraine to Russia. I don’t believe there’s any consensus on that.” Weakening Russia’s military capacity “is a good thing to do,” Mr. Heisbourg said, “but it’s a means to an end, not an end in itself.”

There are other factors that risk broadening the conflict. Within weeks, Sweden and Finland are expected to seek entry into NATO — expanding the alliance in reaction to Mr. Putin’s efforts to break it up. But the process could take months because each NATO country would have to ratify the move, and that could open a period of vulnerability. Russia could threaten both countries before they are formally accepted into the alliance and are covered by the NATO treaty that stipulates an attack on one member is an attack on all.

But there is less and less doubt that Sweden and Finland will become the 31st and 32nd members of the alliance. Mr. Niblett said a new expansion of NATO — just what Mr. Putin has been objecting to for the last two decades — would “make explicit the new front lines of the standoff with Russia.”

Not surprisingly, both sides are playing on the fear that the war could spread, in propaganda campaigns that parallel the ongoing war on the ground. President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine frequently raises the possibility in his evening radio addresses; two weeks ago, imploring NATO allies for more arms, he argued that “we can either stop Russia or lose the whole of Eastern Europe.”

Russia has its own handbook, episodically arguing that its goals go beyond “denazification” of Ukraine to the removal of NATO forces and weapons from allied countries that did not host either before 1997. Moscow’s frequent references to the growing risk of nuclear war seem intended to drive home the point that the West should not push too far.

That message resonates in Germany, which has long sought to avoid provoking Mr. Putin, said Ulrich Speck, a German analyst. To say that “Russia must not win,” he said, is different from saying “Russia must lose.”

There is a concern in Berlin that “we shouldn’t push Putin too hard against the wall,” Mr. Speck said, “so that he may become desperate and do something

truly irresponsible.”

BENTO BOX

Article 5 The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognised by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.

Any such armed attack and all measures taken as a result thereof shall immediately be reported to the Security Council. Such measures shall be terminated when the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to restore and maintain international peace and security .